Eric Michel Religious Society of the Dragon EMRSD, pledging to protect the Graal.

To be a member, you must prove to be Catholic, and you must know about

Arthurian Mythology.

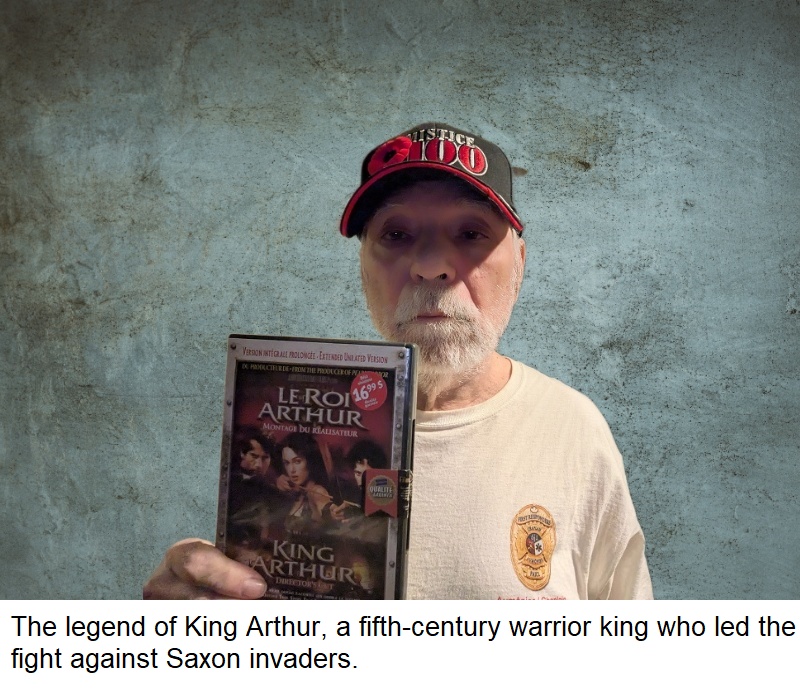

A genuine historical figure is at the core of the Arthur legend; that man was likely a warlord or chieftain living in Britain around 500 AD, based on the early 6th century On the Ruin of and Conquest of Britain (De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae) by St. Gildas, which mentions some of the actions attributed to Arthur but not his name. He really only emerges as the figure we know in the 1130s, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (Historia Regum Britanniae), which contains a blend of fact and fiction. Around the time of Geoffrey, Arthur begins appearing in saints’ lives. The Life of St. Cadoc (Vita Cadoci), written in the 11th century by Lifris at Llancarfan. We’re told that Arthur, Kaye (“Cai”), and Bedevere (“Bedwyr”) are dicing when they see a knight and a lady.

The Eric Michel Religious Society of the Dragon (EMRSD) is not a Templar group, but a singular Franciscan order devoted to the Christ Miracle of Transubstantiation in the Holy Grail, also known as the Eucharist by the Eric Michel Ministries International Third Order of the Eucharist.

Our Symbols:

- The Dragon: symbolizes power, strength, and wisdom.

- The Graal: symbolizes the Eucharist.

- Merlin: symbolizes a Christian prophet.

- Arthur Pendragon symbolizes the chief, principal, and supreme Christ.

- Templars: symbolize protectors of the Graal.

Arthurian mythology can be viewed through a Catholic lens, as it was Christianized over time, incorporating figures like Arthur as a Christ-like figure, and its narratives were shaped by medieval Catholic beliefs, particularly in the quest for the Holy Grail.

Christian elements and influence:

Christianization: The legends were initially rooted in Celtic paganism but were later adapted by Christian authors who introduced Christian themes and interpretations.

Christ-like figure: Arthur is often portrayed with Christ-like characteristics, such as performing miracles, being a benevolent ruler, and having a symbolic “death” and potential “return” to restore order.

Holy Grail: The quest for the Holy Grail, especially in later versions, became deeply intertwined with Catholic belief in the Eucharist (the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine), coinciding with the Church’s development of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament.

Symbolic timing: Some key events in the legends, such as Arthur pulling the sword from the stone, are set on Christian holy days, linking these events to Pentecost, a significant moment in the Christian calendar.

Catholic criticisms and conflicts:

Claims of independence: The legends’ claim of an illustrious origin for the British Church, which was independent of Rome, was a potential source of conflict with the Church’s authority.

“The Damsel of the Sanct Grael” is an 1874 oil painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The work is a version of his illustrations for the Arthurian legend of the Holy Grail and depicts a figure often interpreted as Mary Magdalene, not a character from Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. The painting features the damsel holding the chalice and the host, with a dove, a symbol of the Holy Spirit, above her.

Artist: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

Year: 1874

Medium: Oil on canvas

Subject: The Holy Grail, based on Arthurian legend

Symbolism: The damsel is interpreted as Mary Magdalene, a figure the Pre-Raphaelites were fond of depicting. She is shown offering the Grail, symbolizing spiritual purity, with a dove representing the Holy Spirit above her.

Model: Alexa Wilding was the model for this 1874 version.

The story of the Holy Grail begins with Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin who went to Pontius Pilate for permission to remove Jesus’ body from the cross on Good Friday. Joseph and Nicodemus, who had sought permission from Pontius Pilate, came to Jesus secretly and prepared His body for burial in Joseph’s own new tomb. Imprisoned by the Jewish authorities for his proclamation of Jesus’ resurrection, according to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, Joseph receives the Grail from our Saviour to nourish him — then miraculously escapes from his cell without disturbing the seals on the door. Leaving the Holy Land, he travels to France and then to England, bringing the Grail with him to Glastonbury in Somerset, England. As Glastonbury is also claimed by some legends to be the burial place of King Arthur and his queen, Guinevere, the legends of Avalon, Camelot, and the Holy Grail become entwined.

Chrétien de Troyes

Though Chrétien’s account is the earliest and most influential of all Grail texts, it was in the work of Robert de Boron that the Grail truly became the “Holy Grail” and assumed the form most familiar to modern readers in its Christian context. In his Joseph d’Arimathie, composed between 1191 and 1202, Robert tells the story of Joseph of Arimathea acquiring the chalice used at the Last Supper to collect Christ’s blood after his removal from the cross. Joseph is thrown in prison, where Christ visits him and explains the mysteries of the blessed cup. Upon his release, Joseph gathers his in-laws and other followers and travels west to Britain, where he founds a dynasty of Grail keepers that eventually includes Perceval.

Robert returned to the subject of the Grail as a significant theme in Merlin, where he linked it to the figure of Merlin, whom he had transformed into a Grail prophet who orders the construction of the Round Table as a successor to the previous Grail tables of Jesus and Joseph. Perceval himself is the subject of the Prose Perceval (Perceval en prose), a rare work sometimes attributed to Robert, which presents a revised and completed version of Chrétien’s story while simultaneously serving as a continuation of Joseph and Merlin.