While the Roman Catholic Church officially rejects outright Gnostic-style esotericism, it possesses deep, often hidden or symbolic spiritual teachings (Mysticism, Theosis, Sacraments, Neoplatonic Theology) understood through deeper study, analogy (like Dante), and mystical experience, contrasting with the occult. Key areas include the Disciplina Arcani (early church secrets), the mystical theology of saints (Aquinas, Teresa of Ávila), and symbolic interpretations of scripture (like the Divine Comedy), all pointing to a deeper reality beyond literal understanding, accessible through faith, contemplation, and tradition, not just hidden texts or practices.

Core Esoteric Themes & Practices

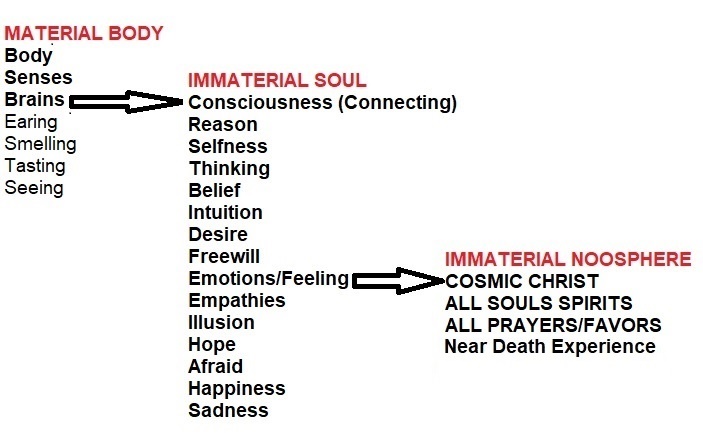

- Mysticism & Theosis (Deification): A central, though often overlooked, teaching is the call to union with God (theosis), transforming the soul to share in divine life, a profound inner spiritual journey.

- Symbolic & Allegorical Interpretation: The Church uses rich symbolism in liturgy, sacraments (like the Eucharist as real presence), and scripture (parables, Revelation) to convey deeper truths beyond literal meaning, echoing ancient mystery traditions.

- Sacramental Theology: Sacraments are seen as channels of grace, actualizing spiritual realities, far removed from mere symbolic gestures, requiring faith and participation.

- Disciplina Arcani (Discipline of the Secret): In the early Church, certain deeper truths (like the Trinity, the Eucharist) were taught only to initiates after baptism, a tradition of spiritual progression.

- Neoplatonic Influence: Scholastic theology, especially in the Trinity doctrine (using terms like “substance,” “hypostasis”), relies on philosophical frameworks for deeper understanding.

Examples of Esoteric Expression

- Dante’s Divine Comedy: An epic journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, viewed as a profound mystical allegory of the soul’s path to God, embodying complex theological and spiritual concepts.

- Saints & Mystics: Figures like St. John of the Cross, Teresa of Ávila, or Meister Eckhart explored inner spiritual states (the Dark Night, the Interior Castle) through contemplative prayer.

- Sacred Geometry & Liturgy: The intricate beauty of cathedrals, vestments, and rituals are designed to elevate the soul and reveal divine order, acting as “mediations” to the divine.

Distinction from the Occult

- Source of Knowledge: Catholic “esotericism” seeks hidden meaning within God’s revelation (Scripture, Tradition) and through grace, whereas the occult seeks power over nature or hidden forces, often through forbidden means, which the Church rejects.

- Purpose: Catholic mysticism aims at union with God, while occultism often seeks personal power or knowledge of future events, a practice deemed sinful.

The Roman Catholic Church does not have “esoteric teachings” in the sense of secret doctrines known only to an inner circle of initiates. Its official teachings are public and accessible, primarily through the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the Pope’s public addresses.

However, the term “esoteric teachings” can be understood in a few ways, which the Church addresses:

- Mystical Theology: The Church has a rich tradition of mystical theology and contemplative practices aimed at a deep, personal encounter with God, such as those associated with the Carmelite order or Ignatian spirituality. These are not “secret” but are advanced spiritual paths requiring dedication and guidance, often involving profound inner transformation.

- Deeper Understanding: The Church acknowledges that some aspects of Christ’s teachings are complex and require deeper study and spiritual maturity to understand fully, often presented through parables or nuanced theological language.

- “Hidden” Doctrines (Historical Context): In the early Church, there was a practice called the disciplina arcani, which involved maintaining secrecy around certain liturgical practices and the precise form of some doctrines to protect them from mockery or misunderstanding by those outside the faith. This was a matter of liturgical secrecy rather than a separate, “esoteric” theology.

- Condemnation of Occultism: The Catholic Church explicitly condemns practices typically associated with “esoteric” or “occult” traditions outside its framework, such as tarot cards, séances, witchcraft, or seeking guidance from psychics. The Church teaches that engaging in these practices is a sin against the virtue of religion and can open individuals to demonic influence.

- Alternative Interpretations (Esoteric Catholicism): There are independent groups and movements that identify as “Esoteric Christian” or “Liberal Catholic” and claim to offer alternative, often Gnostic or Theosophical, interpretations of Catholic rites and theology. These groups are not in communion with the Roman Catholic Church and their teachings are considered heterodox or heretical by the Vatican.

In essence, while the Roman Catholic Church promotes profound spiritual depth and theological study, it rejects the notion of a hidden, Gnostic-style “esoteric” doctrine and warns strongly against practices associated with the occult or secret societies that claim to have such knowledge.

Defenisions:

Esoteric refers to something understood by only a few with specialized knowledge, or something obscure, private, and difficult for the general public; it originates from ancient Greek philosophy distinguishing “inner” (eso-) teachings for initiates from “outer” (exo-) public lessons, often applied to secret spiritual or philosophical doctrines, niche interests, or highly technical subjects.

Our Teaching is EXOTERIC, these are not “secret” but are advanced spiritual paths requiring dedication and guidance, often involving profound inner transformation.

EXOT’ERIC, adjective [Gr. exterior.] External; public; opposed to esoteric or secret. The exoteric doctrines of the ancient philosophers were those which were openly professed and taught. https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/exoteric

Exoteric derives from Latin exotericus, which is itself from Greek exōterikos, meaning “external,” and ultimately from exō, meaning “outside.” Exō has a number of offspring in English, including exotic, exonerate, exorbitant, and the combining form exo- or ex- (as in exoskeleton and exobiology). The antonym of exoteric is esoteric, meaning “designed for or understood by the specially initiated alone”; it descends from the Greek word for “within,” esō. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/exoteric

Gnosis as spiritual knowledge

- The term has been used in contexts of the apostle Paul used the word in the Bible to describe a spiritual dimension of knowledge.

- Gnosis is a form of spiritual or intuitive knowledge, often described as a perfect knowledge that provides liberation from earthly circumstances.

Saints John of the Cross and Hildegard of Bingen are two profound Christian mystics and Doctors of the Church whose “esoteric” appeal stems from their symbolic language and deep spiritual insights into union with God. While they lived centuries apart, their writings offer powerful, non-dualistic perspectives on the spiritual journey.

Saint John of the Cross (1542–1591)

A Spanish Carmelite friar, priest, and a major figure in the Counter-Reformation, John of the Cross is best known for his intense, poetic, and systematic writings on the soul’s journey to God.

The “Esoteric” Nature: His work is often perceived as deep and challenging because it focuses on the painful, necessary process of purification and detachment from worldly affections.

Key Concepts:

- The Dark Night of the Soul: This is his most famous concept, describing the spiritual hardships and sense of abandonment the soul endures as God purifies it of its attachments and sensory desires. This is a period of “unknowing” or “ignorance” that leads to divine light.

- Union with God: The ultimate goal of his mysticism is complete transformation and union with the divine, using the imagery of fire to describe how the soul becomes one with God’s love, much like a log becomes the flame.

- Contemplation: He taught a deep, contemplative form of mental prayer focused on complete docility to God’s movements in the soul.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179)

A German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, and polymath, Hildegard’s “esoteric” appeal lies in her vivid, complex cosmic visions and her holistic understanding of creation.

The “Esoteric” Nature: Her spirituality is characterized by rich, symbolic language and an “theandrocosmic” ecology (dialogue between God, humanity, and the cosmos), which can be complex to unpack using modern frameworks. She also explored subjects like natural history, medicine, and the healing power of elements like gems, which were considered “occult” in the medieval sense of “hidden” knowledge.

Key Concepts:

- Visions (Scivias): At age 42, commanded by a divine light, she began dictating her powerful visions, which encompassed the entire history of salvation from creation to the end of time.

- Viriditas (Greening Power): A central motif in her work, this untranslatable Latin term implies freshness, vitality, growth, and the feminine aspect of God as Creator. It is the persistent, unstoppable power of divine life waiting to burst forth in creation and the soul.

- Cosmic Harmony: Hildegard perceived the harmony and interconnectedness of all things in God’s creation, a non-dualistic perspective that emphasized the inherent goodness of the natural world.

Connection

While they approached mysticism from different eras and traditions (Benedictine vs. Carmelite reform), both saints were declared Doctors of the Church on the same day in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI, recognizing their profound and “perennially relevant” theological contributions. Both offer a path to God that involves a deep internal journey and an awareness of the divine presence that permeates all aspects of existence.

While John’s path to the divine emphasizes detachment and a painful darkness as the crucible for union, Hildegard’s path highlights integration and a vibrant greening of the soul through engagement with the natural world and creative expression. Both, however, point to a radical transformation and an intimate, personal encounter with God that goes beyond conventional religious practice, making their teachings enduringly relevant to modern seekers of deeper spiritual wisdom.

Our Teaching By Brother Eric Michel

Curriculum

- The Johannite Tradition. The term Johannine community refers to a community that emphasized the Gospel of John, which elaborated on teachings attributed to Jesus that were not present in the Gospels of Mark, Luke, and Matthew.

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.The Joannism remain in our Teilhard Universal Christ teaching, belief and practice; all our Theology and our Philosophy are based on two passages of the Bible, first John 1:1-5, In the beginning, was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.This one was at the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and apart from him, not one thing came into being that has come into being. In him was life, and life was the light of humanity. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

- Paul Oneness. And the second on Ephesians 4: 4-6 one body and one Spirit (just as also you were called with one hope of your calling), one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all, and through all, and in all. In one word, CHRIST.

Our teaching is not online, you have to be able to participate in person in the MRC d’Argenteuil Quebec.

Note:

EMMI’s Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults

- If you are lifelong Catholic and looking to learn more about a new horizon

- Member of our Ecumenism

- You need proof that you are baptized, and confirmed, need to state parish name and pastor name, diocese name

- Certificate of your Sunday School or similar document

- We will request a security deposit $$$, that will be freezed for two years